Fluttering on the Surface

Lose yourself in intricate geometric abstractions. Fluttering on the Surface is a solo exhibition of Sarah Mufford’s complex pattern works, informed by Eastern and Western sources.

Mufford’s work invites the viewer to engage with a dynamic interplay of shapes and colours that constantly shift and transform without one element dominating. This sense of movement is enhanced by the artist’s use of negative space, allowing the eye to rest and refocus, creating a sense of rhythm and flow.

Fluttering on the Surface

Sarah Mufford

A response to Sarah Mufford’s exhibition by Associate Professor in Art History and Visual Culture at Charles Sturt University, Sam Bowker

Sarah Mufford’s creative practice seeks to understand holistic processes of visual culture. Her work reveals subtle sensory structures that inform our perception of harmony and balance. Using a ruler, compass and vivid colours, she encourages us to see how geometry, colour, field and rhythmic forms interact as rich spaces for sensory imagination.

Across this delicate, colourful and ambitious exhibition, our vision is intricately interrupted by solid semicircles. Each is isolated from even more complex potential patterns. The visible under-drawing is intentional, for Mufford’s labor-intensive process emphasizes the importance of geometry as a profound foundation, both visually and conceptually. Her reverence for the historic pursuit of geometric forms in art history is drawn from her extensive fieldwork across India, southern Spain, Italy and Iran. Her experiments are related to the Pattern and Decoration (P&D) movement in American postmodernism, which drew on a similar array of sources across broadly Islamic, Persianate, and South Asian art – which were, and still are, collectively under-represented in Australian contemporary art – yet her finished work is distinctly of her own time and place.

Through this ongoing creative practice research, Mufford has studied diverse interpretations of geometric design and the history of sensory perception. Rather than simply copying specific examples or illustrating regional practices, she has compared their objectives and variations through their own contexts, and arrived at a coherence that is entirely her own.

For generations of artists and artisans, mathematics has served as an extension of philosophy, religion and visual culture. Mufford is part of this continuity, drawing from the rich depth and breadth of art history to offer a new way of seeing. Her work is not descriptive, but imaginative, acknowledging sources as a testament to a more connected, coherent model of international creative practice. Sarah Mufford’s paintings are inventions rather than replications, posed on the continuous question ‘what if?’, and moving toward new possibilities.

In reflecting on Mufford’s exhibition, I offer interpretation about four paintings featured in Fluttering on the Surface.

In Jali (2023) the precisely cut structure of carved screens are evoked, drawing from a solution to allow the permeation of moving air through architecture. The jali is a Persianate design, notably preserved in the intricate dark pink and warm red masonry of Akbar’s abandoned capital city Fatehpur Sikri in Agra, India. But comparable structures have been developed elsewhere – such as meshrabiyeh timber latticework screens, shamsiyya gypsum screens, or even Frank Lloyd Wright’s (somewhat brutalist) usonian open-cinderblock walls. Mufford’s approach moves beyond any of those specific contexts. Perceptively, she asks what do we see and feel when experiencing these decorative screens? What was intended by their makers in-situ, rather than those who subsequently disconnected and moved them into the rarified rooms of museums?

Through semicircles, we see blue sky, we see green foliage, we feel faint air in subtle motion.

Ottoman tents were appliqued and embroidered with lustrous threads and luxurious textiles to evoke the sensory ideal of a garden – a landscape transformed on humanity’s terms. As mobile architecture, the illusion of place moved with the tent, even when a new view could be borrowed by the act of re-location. Mufford’s work reminds me of that sensory representation. Her memories are evoked and allude through the ambiguity of abstraction, which is richer than tromp l’oeil realism.

The intensity of Leheriya (2023) acknowledges a similar quality, but this time it is situated via the resplendent textiles of south Asia. The term leheriya is a Rajasthani form of woven fabric, worn as a saree or turban, defined by a persistent wave-like or zig-zag pattern. Across Mufford’s characteristic blue and green semicircles you may discern groups of squares, but moving your eyes between each ‘square’ creates the trickling flow of water, tentatively seeking passage over an open field. Water is heavier than air, and thus far more intense colours have been chosen.

Kashan (2023) situates a geographic point of origin – a city in the province of Isfahan, Iran. However, that place has been informed by centuries of inherited culture and subsequent transformations. It is an analogy for a past and a future as a form of symmetry and asymmetry. When viewing this work, you may note the abstract forms in dark tones are nearly symmetrical against a pale green field. But look more closely at the secretive pattern across the semicircles – are they palindromes?

On a geometric perspective, the immediate present could be seen as a perpetual palindrome, extending infinitely in all directions. This is a critical point underpinning the philosophy of geometric design, allowing extrapolation into the infinite without glitches or disjointed continuity.

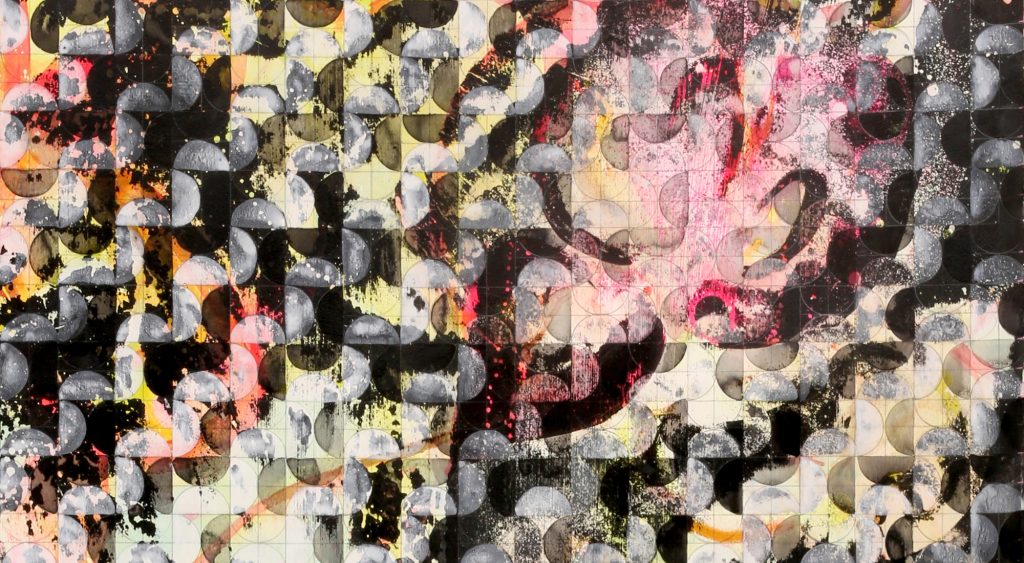

Neshan (2023) is a Farsi (Persian) word meaning a mark or target, or a seal (like a symbol or medallion). Within these billowing, cloud-like forms, notice the negative spaces between the semicircles, and how these form a pattern unseen in the rest of this exhibition, built through gaps like voids on a manuscript. The curlicues of coiling forms seem to trace the rhythmic movements of a murmuration of birds in flight, or the rise and fall of asemic script – that is, graphic forms that resemble words but do not contain their meanings. This type of abstraction was a foundation principle of the Hurrufiyya movement in Arab modernism, yet in Mufford’s work this is not intended as a commentary on calligraphy. Rather, her work is a study of time in motion through abstraction on a geometric frame, in which parallels are invited to be drawn by other observers.

Mufford’s paintings are the result of extended and careful listening, thoughtful observation, critical comparison, and creative practice research towards even more ambitious questions. This is a manifesto for insightful practice, acknowledging diverse sources with respect and attention to their underpinning processes, raising challenges to global art history through contemporary Australian art.